“The bush is our home, our whole life”

Interview with Aissatou Oumarou

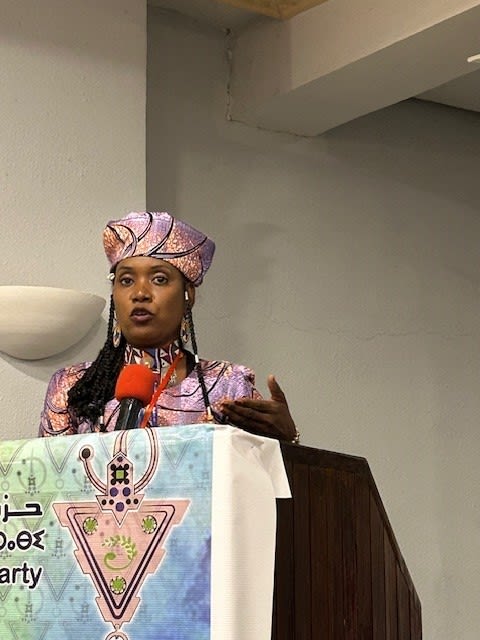

Aissatou Oumarou is from Chad and a member of the Mbororo Fulani (known also as Fulbé, Peul or Fula), an Indigenous community of semi-nomadic Islamic pastoralists. She belongs to the Association des Femmes Peules et Peuples Autochtones du Tchad and serves as the vice coordinator of the REPALEAC, the network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa.

© Aissatou Oumarou

© Aissatou Oumarou

How is climate change impacting your community?

I am from the Mbororo community, which is a pastoral community. We are severely impacted by climate change because we have animals that should be grazing – we are in continuous transhumance: this means that we go from north to south, south to north, depending on the movement of the climate and the weather. Hence the climate change impact in our community is such that there are years where there is a lot of rainfall and there are years where there is little to no rainfall. When there is a lot of rainfall, we must go much further north. During the time when there is not enough rainfall, we are forced to move further south. During this period of transhumance, a variety of problems arise: issues related to the land, inter-community problems, conflicts between farmers and herders. And that's where the impact is felt the most. But there is also the problem of our traditional Indigenous knowledge that is disappearing. This is particularly challenging to us, since we are nomadic Indigenous communities who use a lot of resources from the bush. Everything we do is related to the bush: we eat, work, and live through it. Through the impacts of climate change, we feel we have all the problems of the world to carry on our shoulders.

What does the bush mean to you and your community and which role does it play in the fight against climate change?

The bush for me and our community is our home, our house, our supermarket – it’s our whole life. We live in it; we eat in it – the bush provides us with everything we want. It's our hospital, it's our school, it's all we want. It's there, it feeds us and our animals, our children. But it also allows us to be in symbiosis with this nature, with mother nature surrounding us.

We must regenerate and protect the bush if we are to preserve our traditional knowledge and skills that help us to adapt to and mitigate climate change. I fight to protect this environment, to protect my way of life, my culture, my knowledge – for the sake of my community I don't want my children to grow up without traditional knowledge. I don’t want my children to change their way of life. I would like them to know the ways of life of the Mbororo communities and what defines their culture. For instance, what is it like to go behind the cows while it's raining and come back and have a cup of hot milk? I would like my children to know that. That's why I'm fighting not only for my children, but for my children's children, to perpetuate what is our way of life, which is our identity. I don't want to lose my identity and that's the case for all the Mbororo – this is the case for all Indigenous peoples in Central Africa. I am here as the sub-regional coordinator for Central Africa. We have the Baka People and other communities, such as the Pygmies, who live only in the forest. I also fight for their cultures to be able to survive – this can only happen if the forests and bushlands do not disappear, so that future generations can live on these lands. They must know what hunting and what gathering is. What is it like to build a house or a hut in the rain and take shelter and eat food that we just picked ourselves, freshly organic, naturally in our forest? This is what future generations need to learn if our culture is to survive.

Women from the Mbororo community in Chad. © Aissatou Oumarou

Women from the Mbororo community in Chad. © Aissatou Oumarou

Bush [noun]: an uncultivated or sparsely settled area, esp in Africa, Australia, New Zealand, or Canada: usually covered with trees or shrubs, varying from open shrubby country to dense rainforest.

"The bush for me and our community is our home, our house, our supermarket – it’s our whole life."

Aissatou Oumarou

Semi-nomadic pastoralist communities like the Mbororo mostly depend on crop farming and cattle rearing for their livelihoods - they are thus highly impacted by the effects of climate change. © Aissatou Oumarou

Semi-nomadic pastoralist communities like the Mbororo mostly depend on crop farming and cattle rearing for their livelihoods - they are thus highly impacted by the effects of climate change. © Aissatou Oumarou

Which challenges do you face in terms of land rights? To what extent does the transition from community to private ownership have an impact on traditional transhumance cycles? What are the challenges of managing land, forests and natural resources?

Indigenous peoples are so marginalized that they have little or no access to land, and for Indigenous women it's even worse. So, the biggest challenge is access to land, territories and water, as well as support from local and administrative authorities to minimize the impact of concessionaires on Indigenous territories in the forests and agro-industry in the savannahs. As for the management of natural resources, forests and land, the challenge is to make everyone understand the positive impact that Indigenous peoples have on the environment and the protection of the latter in relation to biodiversity and traditional knowledge.

If you could send a message directly to world leaders, what would it be?

If we talk about the impacts of climate change, well, it's not the high-ranking leader who feels this change, it's us, the communities, who experience all the impacts. While they might be able to notice climatic changes, experiencing floods or warming temperatures in some areas – they don't know that we, on the other hand, are dying every day because of climate change. So we’d like to tell them that they should come at least for a day in the bush, where we live, to see how we live – and if they are really determined to reverse the current trend, they need to work with the Indigenous peoples who are the holders of traditional knowledge and who are able to preserve this environment and protect our planet in a natural and spiritual way.

Aissatou Oumarou belongs to the Association des Femmes Peules et Peuples Autochtones du Tchad and serves as the vice coordinator of the REPALEAC, the network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa. © Aissatou Oumarou

Aissatou Oumarou belongs to the Association des Femmes Peules et Peuples Autochtones du Tchad and serves as the vice coordinator of the REPALEAC, the network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa. © Aissatou Oumarou

Which are the major challenges you encounter in your work and what are the difficulties encountered by the Fulani in terms of governance?

Our difficulties are enormous and manifold.

Given their way of life, the Fulani are already excluded from the education system, which is a conventional Monday-to-Saturday, 7 a.m. to 12 p.m. system - it's not suited to their nomadic lifestyle. So, when a community doesn't go to school, it means it can't read or write, so it suffers. In this case, the community knows neither its rights nor its duties, and so the local communities and certain authorities take advantage of the situation to harm them. As a result, their rights are flouted, and they have no representation in decision-making bodies. So, as the saying goes: anything done for you without you is against you. This unfortunately applies to my community.

Investment is a second issue – there are investors who really want to help us. However, they're imposing lengthy documents on us that we must fill out, but we don't have any training nor experience with these new tools, let alone the knowledge and writing skills to respond to these kind of project requirements. Yet, when they come and say they’re launching open calls for Indigenous people, there are other people who respond. These places get filled quickly, by people who know the needs and corresponding tools very well. But do these funds really go to the community? No, they don't go to the community. The funds that are dedicated to the communities do not really reach them: these are difficulties that need to be addressed. There are many other problems, and, in some countries, the partners do not even go there. They don't make noise there – take the example of my country, Chad. How many partners go there to help the Indigenous peoples? Well, I would say almost none. We must try to change that. So, there are a lot of difficulties that we Indigenous people are facing in this world right now.

What is your take on carbon markets?

We need to be careful and work on solutions needed on the ground – and these will vary depending on the locality, which is why we must be very specific. There are countries that are going to position themselves, there are organizations that are going to position themselves, but we must always see that the grassroots organizations, the community organizations, the Indigenous peoples, are involved and contribute to these systems. And you must work directly with these communities to have real impacts on the ground. That's a challenge.

I come from Chad and feel my country is quite neglected in that sense. The savanna countries in general are not too involved. Instead, countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, and the Central African Republic receive a lot of investments. But is it enough? No, I don't think so. Also, in terms of investments, I think we should not limit ourselves to the already identified countries. When a flood is coming, we are not only going to take care of one room – we must secure the front door first so that the water doesn't get into the house. When it gets into the house, nothing will be spared. If the kitchen is flooded, the living rooms flooded, everything is flooded! By this, I mean that we must start first with the advancing desert, which are the neighboring countries such as Chad, including the Congo Basin which has a part of the desert and a part of the savanna that must be protected. We cannot afford our savanna to turn into a desert – it’s the same with the forest area which must be protected so that it doesn’t become a savanna.

© Aissatou Oumarou

© Aissatou Oumarou

How is the war in Sudan affecting your community?

The war in Sudan is a scourge that weighs on national security in Chad in general. Knowing that the Chad-Sudan border was always a problem, the Peul Mbororos are a little further away from the most virulent part, which is Darfur, but they can be found to the south of Salamat and Moyen Chari. For the moment, they are less affected by the war in Sudan than by the farmer-herder conflicts and the conflicts in the CAR. All the same, there are impacts on cross-border and local transhumance.

Could you tell us more about REPALEAC's work, strategic plan and vision?

REPALEAC is a sub-regional network of 8 countries, with several others applying to join. Our vision is that by 2025, the Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) of Central Africa will participate effectively in the governance and sustainable management of lands, territories and natural resources in accordance with their traditional knowledge, to improve their living conditions while respecting their rights and freedoms. Its aim is to increase and guarantee the participation of IPLC in the management of Central African forest ecosystems, in line with the sub-regional guidelines adopted by the Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC). REPALEAC has adopted a "Strategic Plan 2018-2025" for the sustainable development of indigenous peoples and local communities in Central Africa, in line with the revised COMIFAC 2 Convergence Plan. This Strategic Plan is a result of a participatory process that has engaged the network and its national representations since 2016, and is supported by its partners; notably the German Technical Cooperation (GIZ), the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Forest Partnership Carbon Fund (FCPF) of the World Bank (WB).,

REPALEAC takes action to defend the rights of IPLC, as well as the sustainability of the ecosystems to which they are intimately linked and on which their survival depends. To this end, REPALEAC is developing initiatives to ensure the participation of PACL in national, regional, and international negotiations, and to develop the added value of traditional knowledge in the sustainable management of natural resources.

What are you most afraid of?

I’m worried that a part of our country does not believe in climate change. We also fear that the partners don’t believe in the impacts of climate change on communities and don’t see the necessity to support us in this fight. We are also afraid that the partners will not come to invest directly with us, and instead provide investments to other people who are not directly in touch with the communities. We are afraid that the government will not really be interested in the communities, but instead just focus on its own interests. In the meantime, communities are dying. That is our greatest fear.

© Aissatou Oumarou

© Aissatou Oumarou

What do you hope for?

We believe in our struggle and will continue – therein lies our greatest hope. We can convince people that we have a lot of needs, for which we have concrete examples and solutions. We don't have to make a big effort to have an actual impact on the ground: With as little as a hundred dollars, we can do something that a big organization can't do with five-thousand dollars. Our hope lies in our own strength, and we will continue to fight until we reach our goal.

Footnotes:

This interview was recorded by UNDP Climate & Forests, with support from the UN-REDD Programme, in September 2022 during Climate Week in New York City.

UNDP Climate & Forests assists countries and stakeholders to implement the Paris Agreement by reducing deforestation, forest degradation and promoting sustainable development pathways.

UNDP Climate & Forests systematically promotes social equity, including the rights, knowledge, and inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, to ensure forest solutions to climate change contribute meaningfully to delivering on the NDCs and advancing the SDGs.

© Aissatou Oumarou

© Aissatou Oumarou

Interview: Nina Kantcheva | Editing, visual layout, translation: Roxana Auhagen | Social media: Sila Alici Kavuk

Copyright portrait & community photos: Aissatou Oumarou

Other photos: as noted.