Fighting for the Amazon and Humanity: Chico Mendes’ legacy lives on

“At first I thought I was fighting to save rubber trees, then I thought I was fighting to save the Amazon rainforest.

Now I realize I am fighting for humanity.”

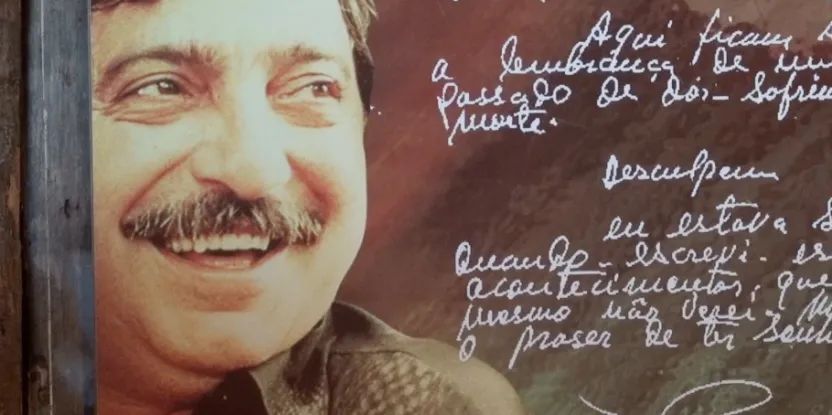

Chico Mendes, 1944-1988

These words were spoken by Francisco Alves Mendes Filho, better known as Chico Mendes – the famous Brazilian rubber tapper, union leader, and environmental activist who became a global symbol of the struggle to protect the Amazon rainforest and the rights of its traditional and Indigenous communities.

Chico Mendes: Defender of the Amazon and its people

Chico Mendes, born into a rubber-tapping family in Xapuri, in the Brazilian state of Acre, grew up working as a seringueiro (rupper tapper), extracting latex from the Seringueira tree (Hevea brasilensis) in a way that preserved the fragile equilibrium of the Amazon rainforest. As large-scale deforestation surged in the 1970s and 1980s during Brazil’s military dictatorship, he united rubber tappers – women, men and children – into unions and led peaceful resistance called "empates" to resist destruction driven by cattle ranching, logging, and government-backed development projects threatening the livelihoods of rubber tappers and Indigenous peoples. His advocacy for Extractive Reserves gained international recognition but his growing influence made him a target. In 1988, he was assassinated at his doorstep by rangers opposing his work. Though he did not live to see the creation of his life’s work, the Extractive Reserves – established shortly after his death – his legacy endures, inspiring policies that continue to protect the Amazon and its people today.

A call to the world: Protecting the Amazon, protecting our future

His cousin, Raimundo Mendes de Barros, also a rubber tapper and activist, has spent his life to continue Chico’s fight for the conservation of the Amazon and the rights of its traditional and Indigenous communities. For 79-year-old Raimundão, as Chico’s cousin is known, the fight to preserve the Amazon is not just a local struggle – it is a global responsibility. “As someone born and raised in the forest, and as a lifelong defender of it, I want to make a strong appeal to the international community – especially those with access to resources,” he says. Raimundo’s message is clear: urgent investment is needed to restore degraded areas and promote sustainable practices that allow people to use the land without destroying the forest. He believes that with the right tools, economic development and conservation can go hand in hand. “Through mechanization, fertilization, quality seeds, and technical assistance, we can grow our economy without destroying what remains,” he explains. By focusing on replanting native species and restoring lost ecosystems, he sees a way forward – a future where the forest thrives alongside those who depend on it.

Raimundo Mendes de Barros, also a rubber tapper and activist, has spent his life to continue Chico’s fight for the conservation of the Amazon and the rights of its traditional and Indigenous communities. Photo: Government of Acre

Raimundo Mendes de Barros, also a rubber tapper and activist, has spent his life to continue Chico’s fight for the conservation of the Amazon and the rights of its traditional and Indigenous communities. Photo: Government of Acre

Raimundão recently participated in an event in Acre’s capital Rio Branco that was convened by the state’s government to discuss how international climate finance from carbon markets can be distributed equitably among stakeholders to recognize their role in protecting Acre’s forests while also strengthening measures to reduce deforestation: “We have come together – extractivists, Indigenous Peoples, river dwellers, technicians, and government representatives – because defending the Amazon is a shared responsibility, not just for those who live here but for all of Brazil and the world. As we prepare for the next phase of a major project benefiting traditional communities, it is crucial that the government continues supporting these discussions. I am encouraged by the solidarity and commitment in this gathering and hope our efforts lead to real opportunities that improve lives, protect the forest, and combat global warming.”

"The impact of climate change in the Amazon is immense"

The Amazon is facing unprecedented environmental challenges, and those who have lived in the forest for generations are witnessing its rapid transformation: “The impact of climate change in the Amazon is immense, and I must say, it will take time for people to adapt to what is happening,” says Raimundão, who is also lifelong resident of the Chico Mendes Extractive Reserve, a protected area established in 1990 to support sustainable livelihoods for traditional communities, such as rubber tappers, while preserving the surrounding Amazon rainforest. The signs of climate change, Raimundão explains, are becoming impossible to ignore.

One of the most alarming issues is the growing scarcity of water. “We are already seeing water shortages – not just in my area but in many others,” he says. In response, communities have been forced to drill artesian wells as deep as 40, 50, even 60 meters – something they never imagined would be necessary in the Amazon rainforest

Extreme heat is another harsh reality. “Some days, it’s unbearable,” Raimundão admits. “I’m old and have health problems, so I can’t stay in the fields past 8:30 in the morning. I have to start working at 5:00 a.m. just to get a few hours in before the heat becomes overwhelming.”

Survival in a changing climate

The crisis extends beyond humans – wildlife is struggling too. “We are witnessing hunger and thirst among forest animals. They are traveling for hours just to find water,” he says. At the few remaining water sources, animals like pacas, armadillos, and monkeys gather in desperation. Food scarcity is also driving wildlife into human spaces. “Animals are invading people’s homes looking for food. At my house, we have to keep our chickens inside because if we leave them outside, the monkeys will eat them.”

Unexpected changes in wildlife behavior are also causing concern. “We are seeing new species, like wild peccaries, appearing in our region. They never used to be here, but now they’re everywhere, even attacking people,” Raimundão explains. He recalls a shocking experience from the previous year: “While returning from the Brazil nut harvest with my children, we encountered a group of aggressive peccaries in a rubber tree grove. I have worked in the forest my whole life, including in Bolivia, where there are many wild pigs, but I had never seen them behave like that before.”

For Raimundão, these changes paint a clear and troubling picture of the future. “Climate change is affecting everything, and it will take time for people to adapt because no one is left untouched by what is happening.”

Keeping the next generation connected to the forest

At home, Raimundão’s two children – a son and a daughter – are following in his footsteps, involved in the work of conserving the Amazon. But they are among the few. “The vast majority of young people have gone in a different direction,” he deplores. “Many have become cowboys, spending their days riding horses and herding cattle. Others, sadly, have turned to drugs.”

This growing disconnect between younger generations and traditional forest life worries him. He sees an urgent need to inspire them to continue the fight for conservation. “That’s why I have high hopes for this project we are discussing. I hope it gets renewed and that we can secure the resources needed to raise awareness among the younger generation,” he says. “We need to inspire them to join their parents and elders in defending the environment and taking care of our reserve.”

Yet, modern distractions are pulling them away. “Right now, they are being drawn in by cell phones, television, and the illusion of an easier life,” Raimundão explains. Many see cattle ranching as a more attractive alternative because they lack encouragement to stay connected to traditional ways – tapping rubber trees, harvesting Brazil nuts, and living sustainably in the forest.

Educating the youth: The key to preserving the Amazon

For Raimundão, the key to reversing this trend lies in education and engagement. “We need skilled professionals to help educate and raise awareness among our youth,” he emphasizes. Schools, he believes, could play a crucial role. “We need to use the things they already enjoy – sports, celebrations, social activities – as opportunities to engage them in environmental education. That way, we can integrate conservation into their daily lives in a way that resonates with them.”

By reaching young people where they are and showing them that sustainability is not just a responsibility but a viable way of life, he hopes to ensure that the next generation carries on the fight to protect the Amazon.

Photo: Lou Gold

Photo: Lou Gold

Photo: Forest News CIFOR

Photo: Forest News CIFOR

Photo: Fabiano Carnavale

Photo: Fabiano Carnavale

The Amazon’s fate is the world’s fate

Chico Mendes legacy, also driven by his cousin and others, reminds the world that the Amazon’s survival is not just an issue for those who live within it. “What is happening here affects the entire world. Saving the Amazon means saving our planet,” Raimundão warns. The rainforest is a vital regulator of the global climate, and its destruction will have far-reaching consequences. “The forest is essential for maintaining ecological balance and stabilizing the climate – not just for those of us who live here but for cities and people everywhere.”

His plea is urgent and resolute: “I call on both the national and international communities: support us in protecting the Amazon. Because in doing so, we are protecting the future of humanity.”

Interview in Acre with Raimundo Mendes Barros: Ângela Rodrigues and Uêslei Araújo

Author: Roxana Auhagen, UNDP Climate and Forests

Photos / Footage: Government of Acre